Robin Sewlal details the importance of journalism and media freedom in the digital age of democracy

As we commemorate Media Freedom Day, it’s time to be mindful of that which has transpired since that fateful day in 1977, reflect on what it precisely means to report in a free dispensation and act with the necessary fervour.

The media is too powerful and important an institution to be given scant regard in this 20th year of democracy. The media cannot and should not operate in a vacuum.

It is the lifeblood of society’s development and, accordingly, has to be the pulse of the people by representing their best interests at all times.

It’s an onerous task but one that can be accomplished, provided the media addresses the clutch of challenges that confront it continually.

Uppermost, the right to media freedom is entrenched in our much-vaunted Constitution. But we must remind ourselves that it is not an absolute right. In fact, no right is absolute.

The right to media freedom is competing with a range of other rights that rank equally. Moreover, the right afforded to the media is accompanied by a basket of responsibilities. A prime example is the duty of the media to respect an individual’s right to privacy as embodied in section 14 of the Constitution.

In a similar vein, it’s incumbent on the media to respect the dignity of those it reports on, lest it faces an action premised on defamation. Ethics, morals and values have to underpin the work of a journalist when ferreting out his or her next story. The power of the pen and the might of the microphone cannot be underestimated. Journalists, therefore, have to be circumspect when going about their daily tasks.

The media’s responsibility to report in a sensitive and sensible way is sacrosanct. Integrity is the hallmark of excellence in journalism. To this end, it’s both the right and duty of the likes of civil society, captains of industry, industrialists, trade unionists, government, sporting personalities, activists, religious leaders, as well as everyone connected with the business and practice of journalism, to ensure the media reports in a fair, balanced and accurate manner. Nothing less will suffice.

It follows that the media runs the real risk of falling into the unenviable trap of self-censorship when it operates outside the tenets of quality journalism. Just as dangerous is the media itself becoming gatekeepers of what it should or should not provide coverage on.

In this age of digital democracy, social media has infiltrated in no small way. It is in actual terms not a true threat as it does not equate to journalism. But it does place a heavier onus on journalists to provide better content, with a compelling context and of contemporaneous value. Richness in stories depends on covering local issues in an enterprising manner.

Though audiences are increasingly becoming cosmopolitan, the element of “localness” will always hold sway. Issues in peri-urban and, more especially, rural terrains need to be prioritised on journalists’ assignment sheets. They cannot be mere “sound bites” or fillers in newspapers, but should demand concrete and comprehensive coverage.

The follow-through of stories that are the greatest concern to communities is pivotal. Industries that get very little coverage require greater attention. These include maritime, mining and agriculture.

Equitable treatment of issues by journalists ensures fairness.

The Oscar Pistorius case has underlined this journalistic principle. South Africans wait with bated breath on the way the media will in future handle cases involving not-so-famous people.

Further, the media will not be exercising its freedom appropriately if it does not carry a multiplicity of voices of ordinary folk who can add character and colour to stories. But sources of information have to be credible.

Digital migration is scheduled to take place in mid-June. The biggest challenge since this transformative move would be the availability and accessibility of quality content.

The opportunity on the horizon would be an enhanced focus on development journalism. There are far too many issues in the country that require the active intervention of the media by cajoling authorities to address the proper delivery of basic services.

Over and above the advent of the digital era, dynamics within (and even outside) the journalism fraternity call for ongoing refresher training of journalists. It surely cannot be business as usual if the media is to take its freedom seriously and stridently.

New methods of gathering, processing and presentation of news mean journalists have to be on top of their game in telling stories. Resource-strapped newsrooms need to find smarter ways to serve their audiences without compromising on standards.

The increasing number of cases in society that generate ethical dilemmas, along with the galloping pace of new and amended legislation, signal the need for the development of skills and competencies at all levels in the media mix.

Closer communication and cooperation between the media industry and institutions of higher learning need to be reignited.

Just as much as I argue for the media to demonstrate professionalism in the crafting of stories, it is critical for journalists to be afforded respect and given space to perform their functions.

As the fourth estate, the media plays a fundamental role in contributing to the democratic direction of the country. Threats and attacks on journalists are a sure sign of the perpetrators not appreciating and understanding the role of the media.

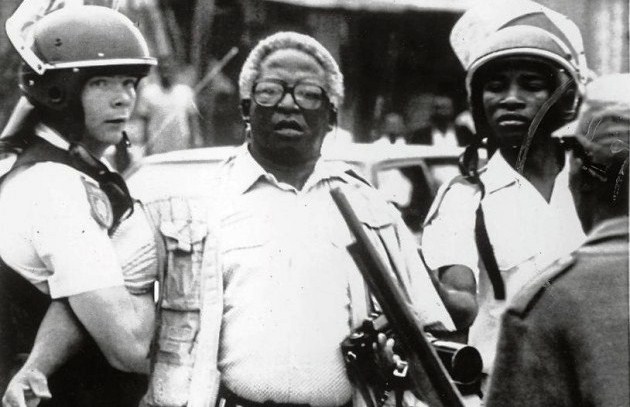

In recent times, one of the most common threats to media freedom has been the willy-nilly confiscation of equipment belonging to photojournalists. A democratic South Africa can ill-afford such blatant interference.

Media freedom cannot be hindered, but it cuts both ways. The media has to up the ante if it is to enjoy continuous support. By the same token, all stakeholders should take steps to advance, not antagonise; stimulate, not stifle; and promote, not purge media freedom.

To do otherwise would be seen as failing in our civic duty to society at large.

Sewlal is the associate director of journalism at the Durban University of Technology and a commissioner at the Broadcast Complaints Commission of SA.

Pictured: Photojournalist Peter Magubane is detained by police during a riot in 1986.

Picture: Peter Magubane Archives

This story appeared in The City Press on 19 October 2014.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Durban University of Technology or its Division of Corporate Affairs.